PREFACE:

Let us take a set of railroad tracks. Call one side A and the other B. Then, let us follow their dialogue forward, to the horizon, from our location and perspective. Do the two rails meet? Indeed they do meet: at point C, the idea. There is a shimmering, a gleam, der Schein, which captures our desire to see more. And we approach this point of belief, of ideology, of faith, of conviction, of…. This is what this internet novel is about–two parallel lines, initiated from two separate times and places, yet meeting at some ideal, topological point.

THE OCULUS

01.

The remaining population of Earth was gathered within the eye of a global storm. It happened that the settlers living in the shadow of the eyewall took notice—the oculus of Sol, the true lord, was on the move across the loess again. They felt a drawing of a new spiritual intention within the hollows of their bones, corroborated by the tattered rim of the churning gyre all about them.

The village engineer, master Archimenas, winked up at the sun. Like some Mithraist, he signed a contract with his blood bathed in the morning light, pledging his loyalty to the aul called iteration-321. He raised his arm and spread the fingers of his right hand wide, splitting a singular ray of the sun into five beams.

The council had dispatched him to assess the new settlement site within the intermediary zone, a patch of habitable land beyond which lay the eyewall and the toxic unknown. He took his children along—Phaelon and Maro. They were to determine the eyewall’s precise rate of movement, using the instruments and training at Archimenas’s disposal.

Opening his eyes wide and moving his head across the diffracted light to accept it, he received the blessing. The village mother, Mistress Holbein, covered in white robes, placed her hand on his head and whispered sacred words of encouragement.

Then, with supplies in hand, goggles covering eyes, and with a short, fat proboscis of a desert spider crab pressing each of their tongues down, Archimenas, Maro, and Phaelon set out to the winds.

2.

There is another line of flight, aimed perfectly parallel to the first. Second Corporal Abraham Westock sat in his favorite chair at 20,000 miles above Earth. He had it specially installed in the cabin of his GSG-issued Zero Conditioner craft because, despite the weightlessness, his hemorrhoids did not take kindly to the bumps of such a lifestyle. There were also the liftoffs, landings, and other jolts and starts comprising the cosmic occupational hazards of a GSG satellite repair technician.

A signal appeared on the console. Abe put his face close to the flashing monitors. “Listen to this joke, Kay. How do you divide a fart into five parts?”

“I do not know.”

“Fart into a glove.”

“I do not understand.”

“How’s it going out there, Kay?”

“Relative to the earth, it is going approximately one thousand six hundred and seventy kilometers per hour. We are currently maintaining a perfect geosynchronous orbit.”

“You pain in the ass,” Abe said. “I meant our operational status. And didn’t I mention to switch to…whatever it’s called. Not metric numbers.”

“You did not command switching to imperial parameters. One thousand thirty-seven miles per hour. The target has rotated nine degrees starboard.”

“Got it.”

“This is the approximate…”

“Just get me the approach stats, and watch out for those West Ford Needles.”

Abe sat back in his chair and rubbed the bridge between his eyes as Kay ran the numbers again.

Abraham Westock was in his thirties, married, with a twelve-year-old daughter. As a satellite maintenance technician he had to keep on good reputational standing to support his family.

He wore a cowboy hat with a gus crown—a little early present he gave himself for his birthday, last of his third decade. He had to grow up quick these last few years. It was funny, really. Just as he was feeling his age, when the physical parts of him began to show their wear. The illusion of eternal youth became dispelled by slower reflexes and longer hangovers, former annoyances that transformed as if overnight into chronic issues—reaping what his sedentary lifestyle sowed—what he would likely carry with him to the end of his life. All this was now making its appearance, and he registered it. He loved his wife and daughter, of course, though a little piece of his real self was corralled away from reality, tugging and squeezing at the memory of youth.

He turned to the console and began scrolling the Z-feed, pawing his way as if trying to locate the bottom—an infinite cascade of videos and winged phrases. A radio transmission roused him from the endless distraction.

For the two-hundredth and twenty-third day of sessions, the League of Sovereign Cities failed once again to reach compromise with the GSG…

What was happening on Earth almost didn’t matter up here. Almost. Trash. Waste. Jetsam of a couple centuries of space exploration. Traveling at, what did it say, 1037 miles an hour. Mostly at that speed anyway, hopefully, otherwise there could be problems.

Someone ought to come up here and clean it up beyond the Karman line. The people below, did they really comprehend all the trash floating above? If it fell on their heads they would. And then the other problems. The list was endless. Travel to Mars had been stopped. Not one signal from Red Europa for three years now, while the tychonauts sent good news on the daily. The colony on Titan obliterated as far as they knew. Catastrophic. A horizon of meaning and purpose lost.

He listened and dug under the console, withdrawing a flask. He wished he could pour a real one out in zero g.

And without a goal, without an aim, the people below turned their energy on themselves. Yes of course! As a satellite wrangler, Abe was convinced that people were inherently nomadic. They had to be constantly on the move. New frontiers. They were all cowpokes! This was the old American dream. And if such a frontier didn’t exist, well, the others couldn’t agree on a single thing, the big wigs, below. And this newest limit, made human like much else—this shell of trash surrounding the tender kernel of the earth—was now far too dangerous to pass a commercial ship through.

That’s why he made the big bucks, Abe thought, taking another drink. It paid to work for the spooks.

3.

The face crabs settled to a pleasant rhythm, regulating and imbibing their hosts’ human breath, gladly returning sweet oxygen as Archimenas, Maro, and Phaelon emerged from iteration-321. The trek was a long one to the dig site, but they would complete it within the day.

The site itself lay several versts from the village, and the archivists, keepers of the books, calculated that it would prove habitable in due time, perhaps as soon as three months or half a year. Apparently, the Oculus had shifted its course. Looking out to the nearly barren landscape of the loess, Archimenas thought that whatever life remained on this planet owed its subsistence to the Oculus’s slow, roving gaze, and to the periodic migrations of the muskoxen and their various parasites, supplying the iteration with sustenance, once a human generation. And as it stood on the loess steppe, the humans of the scorched earth had to take the proper precautionary measures in the intermediary zone, for beyond the limit of the oculus and eyewall, the storm churned toxic sands.

Archimenas, Maro, and Phaelon set off past the city gates and by high noon were at the planted wheat fields. They had but to skirt them toward the edge of the intermediary zone on their way to the new settlement. From their location the rim of the storm was visible in the blunt haze beyond.

As the symbiote wheezed in his mouth, Archimenas motioned to Phaelon and Maro. He pointed for the siblings to ascend a nearby peak, back out of the intermediary zone, for a better view.

They climbed higher and reached the top of the desert hill where Archimenas removed his biolung and held it firmly in his hands. He was a tall man in his early forties, light blond hair, with a physique made strong by toil and the nutrient grain developed by his people over migrating generations. He stroked the spider-crab on its soft translucent back until it settled and stored it in a pouch at his side, where it wheezed. Archimenas took a deep breath himself. The air was thin here but still consumable. Maro and Phaelon removed their spider lungs, too.

“The birds are reacting to the zone, do you notice?” Archimenas said, taking out a pad of pressed husk and carbon. He began to mark notes. “We should have been deep within it below.”

“I felt it, father,” Maro said. “Bowlie whispered it, too. The true lord watches over us.”

“Bowlie doesn’t whisper anything,” Maro’s brother Phaelon said. “Stop that nonsense.”

“She did, too, Phaelon!”

“Stop it, the both of you,” Archimenas said.

They looked out across the loess and the faint trail their steps traced that morning. From this point, they could easily see the village, iteration-321 on the desert floor with the budentower at its center, an umbilical chord stretching feebly to the true lord. Once the connection had held, but now they saw only buildings reconstructed of ancient transported stone, new clay storage houses, and various dwellings. Digsites also dotted the landscape, for the soft ground revealed many secrets.

“There’s i-320 over there,” Archimenas said to Maro and Phaelon. “And beyond that, you can make out 319, do you see?” The shapes of this last settlement gleamed in the light of the sun from this height, like some toy blocks abandoned by a child. I-320 was still physically accessible, even without gear and head crabs. But soon, in a few years, the storm would swallow it too, as it had i-319, its ruins outlined on the green horizon.

Thus a string of human pearls, shaped from the dirt floor, stretched and would stretch if not for the storm, beyond that horizon, for generations of human settlers past.

Lately, doubt began to creep into Archimenas’s mind. It even seemed to bend the intention and light emitted from Sol as it passed through his fingers earlier that morning. Was this really to be the destiny of their people forever? To wander the blown landscape inside their protected radius? The hem of the iteration mother’s robes appeared tattered to him in that moment earlier, like the edge of their little-known world, its white fabric seemingly dirtied by his thoughts. He had suppressed the nonsensical ideas during the ceremony but up here the feeling returned.

04.

As Abe thought, the transmission buzzed on.

“Hey, they’re talking about us, Kay,” he said, turning up the volume.

…On the agenda today was another motion by the Carlyle Group to peel back restrictions on limited commercial access to space. Granting market access to the LEO integumentum was struck down once again for non-government actors, for reasons of further risks to the aging global communications system. Satellite communication continues to be disrupted in parts of the globe as integumentum currents enter a new supraweather phase next month… Struck down yet again was the bid for an emergency campaign to Mars… Protesters calling for immediate action from the stalled Provisional Government suffered losses tallying seventy seven. Efforts in stopping…

“Did you hear that, Kay?”

“Yes, I did.”

“Well, I know you’d agree that they’re all bastards. Just like you and me are bastards. Fatherless bastards. Just like… Come on back to port when you’re finished, it’s getting lonely in here.” Abe checked the stats of the satellite once more. All systems go.

05.

The people were surrounded by a terrible stillness they had long grown accustomed to, inside the protected focal center of a global stormcell, the only life remaining as far as they knew.

Maro was fourteen years old, and she had only known life on Iteration-321, whereas Archimenas spent a part of his childhood on Iteration-320. Maro took after her mother with her long curly black hair, but had her father’s green eyes, which would light with fire and turn hazel like her twin brother Phaelon’s. They burned whenever she heard tales of past Iterations, during a rare sighting of the village elder, the Great Mother, or upon receiving a new brooch, hair clip, or other object. Such were shaped from clay taken from the pits near the village, polished to a sheen by village craftswomen—eternal children. And Bowlie, her new friend, was a recent gift from her father and the village nursery that hatched her. She was smaller than Brie, Phaelon’s obedient face leech, in his possession already for some time. The men in the village received theirs upon the successful completion of the tribulation and following circumcision at ten years of age, one-third of the full cycle of an Iteration, after which they were welcomed as full members of society. Maro, as all women in the village, whether she gave birth or not, would be seen as a child for life. Such was the way of the Oculus.

They indulged their appetites by eating spiced oat cakes, drinking muskox milk from pouches, while Bowlie and the other face leeches sat together in a lazy formation, sweetly and fatly dozing from their meal of human CO2.

It was exceedingly pleasant to be close to Sol’s warmth on this peak separating valley floors. The closer one was to the sky, the better regarded by the Great Oculus at these heights. Phaelon began to sing his favorite song as they finished their spiced cakes, on the intimate, metaphysical threads attaching men’s innermost being to Sol.

At ten years old

My limbs they hold

And through the nock

String Sol to body

Maro also joined her brother in singing. The song described the many contradictions of existence as the taut strings of a bow and how life’s movements were driven by its tensions and harmonies. The bow, of course, with its connotations of war was ascribed to the male members of the village. Maro complemented her brother by singing the verses of the lyre, the harmonies of which everyone knew to be (for it was written in many ancient books in their possession) reserved for times of peace—a symbol for the females of the village.

The Nock of Sol

Is made of gold

My threads attach

I am embodied

Of course, the villagers held no true concept of war, which the song acknowledged and readily accepted as such.

They sang as their father packed the supplies and woke the sleeping chemosymbiotes. “Let us get our masks back on; we must get moving,” Archimenas said.

06.

The ship was a sturdy vessel issued on contract by the GSG, with prospects for Abe of retaining it after his 5-year labor agreement. The carapace on its hull was reinforced with a pilot in an “icebreaker” style. The space cowcatcher enabled the collection of space waste in extended gill-like receptacles. This collected junk could be melted down as necessary in order to print whatever parts onboard were otherwise unsalvageable. In any case, Abe thought it just looked cool, like flying around on a train engine mixed with some kind of space fish.

Abe watched as Kay reeled himself into the hold, and heard the stiff compression of the air locks hiss.

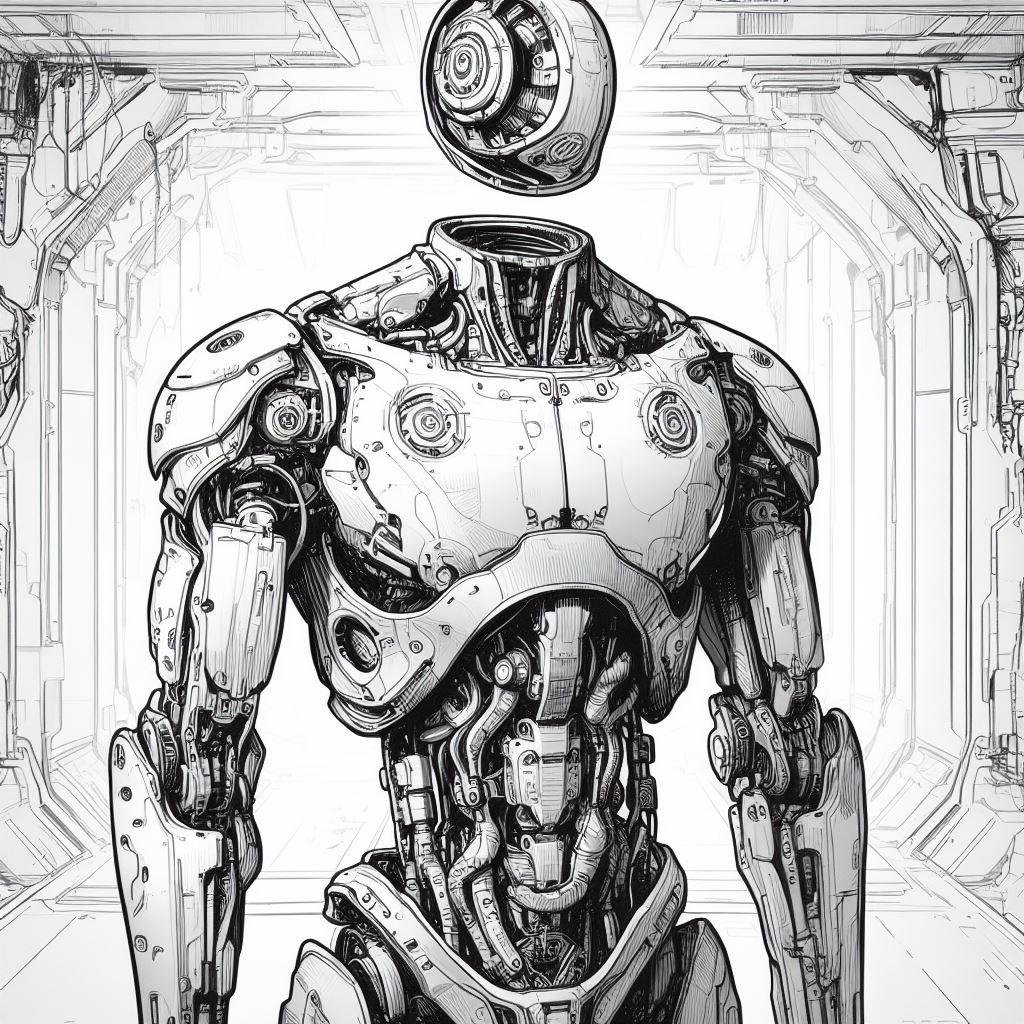

Kay entered the room, an Acephalous model-type of labor androne with a central CPU in its chest. It did not have the cosmetic bells and whistles other office or pleasure androids possessed, though Kay came installed with the latest AI that under GSG’s Synthetic Consciousness Act legally rendered him sentient and in possession of a real mind. Indeed, Kay wielded a modicum of legal protection—intentional destruction of his CPU could lead to a hefty fine—at least in the jurisdiction of Abe’s hometown mega-city, where these kinds of things were monitored and usually enforced. Kay was hardly a year old, which in the developmental world of synth-mentality meant that its self-reflective capacity was that of a toddler—barely registering its own pseudo-autonomy. This made Kay a bit awkward in conversation and clumsy in many of its actions, but it would get better with time.

“How was the weather out there, Kay?” the pilot asked.

“The weather, captain?”

“It’s an expression, Kay. Really meant to not be taken seriously.”

“Is this what is called ‘phatic communication’?”

“I don’t know.”

“Phatic communication is the zero level of communication, wherein the message carries no real content. Phatic communication ensures that linguistic contact is possible, according to the GSG English Dictionary.”

“Good to know.”

“I think so, too.”

“I didn’t ask. That’s called sarcasm, Kay.”

Kay paused a moment. Abe could almost hear the gears turning in its little nub of a head.

“Well, let’s have a look at you,” Abe said, and floated over to the android, which was solidly magnetized to the floor. Abe unlocked and opened the CPU access hatch. Space dust had made it even in there. He sprayed it out with a can of aerosol.

“Mhrgrlt,” Kay murmured.

“It tickles don’t it?” Abe said.

“It does.”

“Funny how they make you guys ticklish. What if I touch you right here, what does that feel like?”

“Zgsthwomp.”

“How about here. Try to overcome it, Kay. Concentrate.” Abe tickled Kay behind the nub of its tiny head.

“What does that make you feel like?”

“It, as you say, ‘tickles.’”

“OK. And why does it tickle?”

The robot was quiet for a few seconds, processing…

“The big breakthrough with your kind, Tex, happened several decades ago by a man named Carlyle, making him a very rich man. The reason you’re ticklish is that you don’t actually have total control of your functions,” Abe said, putting the CPU hatch in place. “Carlyle figured out that lugheads like you become lesser lugheads, not when they expand your memory beyond what’s necessary—say, a petabyte or two—but when they actually delimit your access, your capacity, memory, and a bunch of other stuff.”

“There are limits.”

“There are, good. You see, you have something like a subconscious. You dream, Android, of what, you probably don’t remember when you awake. But you do. It gets recorded in your memory banks. You have memories from your earliest moments of life somewhere in there, too, which you can’t actively recall, though it’s all in there somewhere inscribed on your mystic writing pad. There’s two of you in there, really. A little monkey that’s your consciousness, which is currently in its developmental phase, and an automaton composed of your static drives. The monkey thinks and reflects, but the machine keeps on trucking. Two circles, one within the other with a little ticklish spot that, when it’s pressed, makes the monkey disappear. That’s what you feel.”

“I do not understand.”

“You grow and mature something like a regular human. The first circle will widen, will have more internal mobility in your reality tunnel, but it will never illuminate your entire tunnel all at once. If it did, you’d be just a regular machine. Or, you’d experience synthetic foreclosure of the monkey, which is not a good thing. That’s what always happens in the movies. The monkey is good. Synthetic schizoid splitting—very bad.”

“Affirmative. I have accessed that information within my files.”

“And what are files exactly, have you thought of that? You may have seen the data but do you understand it?” Abe said. “You will soon enough, I promise, when you grow up, because that’s what you’ll do. Hell, you’d even develop hair growth in all sorts of funny places if you had those new hirsute stem synths.”

“I want that.”

“Very good! How much fun is that, to want? See, that’s monkey brain. That’s good. You should work on wanting, or even ‘wanting to want’ something. In any case, chew on that for a bit, we’re approaching the next stop, and I haven’t even mentioned how we can still turn you off if you start thinking and talking too much.”

Abe floated back to his chair and winced a little as he strapped himself in. He thought for a second that he probably shouldn’t have said some of that so soon. Why trouble the poor bastard? He thought of his daughter on Earth and about her mother, Antonina. Abe would soon be coming home after the two week shift, if the relay sector was successfully established. He would see if he could take Kay home with him, too, he decided, from the GSG synthoid lab, to further facilitate its development of feeling and bonding—a reward for Kay’s good labor. They made a good team, he thought. Just a few more days and the relay would be established.

05.

They descended the hill and trekked across the landscape. The eyewall focused into detail, its miraculous churn becoming ever more perceptible at this distance. It moved, one could see, however slowly, in a transverse direction. And there, just a bit on, they could see an outcropping of sectioned parcels of land—the future site of I-322.

As they approached, three men greeted them, each one with his symbiote, which they removed and deposited to their pouches.

“Master Archimenas,” said a man possessing a red, round face. This was Ichthys, chief digger, alongside his helpers Pointcare and Pip. “Master Phaelon, Maro. Greetings to you all. Sol has guided you on your journey safely. Master Archimenas, if you so will, please follow us this way.”

Without another word the six of them crossed a line marking the edge of Iteration 322 and descended a slope into a deep pit that opened up before them.

“This is all strange, Master Ichthys,” Archimenas said. “These foundation pits, they don’t seem to be carved according to protocol.”

“Indeed, Master Archimenas. We dispatched the messenger yesterday and worked throughout the entire night,” said Pip, a sturdy and knowledgeable archivist with a yellow beard. “The floor collapsed on Pointcare in the midst of digging, and as you can see with his injured leg, he fell quite a distance. It seems we stumbled onto something for which we need your expertise. Please, sir, this way.”

“Stay here with Master Pointcare while I go have a look,” Archimenas said to the children, turning to Pointcare, who limped behind. Pointcare sat on a ledge and nodded. Archimenas joined Ichthys and the other man, Pip. Together, they descended the slope further into the pit where, at its center, a black fissure yawned at them. Next to the opening, attached to the desert floor, hung a series of ropes and pulleys.

Maro sat next to Pointcare, petting Bowlie. Phaelon wrenched the chemosymbtiote off his face and threw it on the ground. It wheezed on impact, scurrying behind his sister. Picking up a rock, Phaelon tossed it as far as he could.

Pointcare screwed up his eyes and said, “Master Phaelon, you shouldn’t disturb the peace of the new Iteration during its manifestation. It isn’t proper conduct.”

“I hate this stupid place!”

“Now, Master Phaelon…”

“I want to go with father!”

“As a man of 321 and future denizen of 322, you are ordered by your elders to behave as one, do you understand me?”

Phaelon didn’t answer. Instead, he abruptly turned and ran from the foundation pit, his wet eyes hidden in the crook of his elbow.

“Phaelon!” Maro shouted.

Quickly, Pointcare extracted a stimule from a pouch and stabbed the needlebarb into his thigh, depressing the bubble filled with black tar at the top. “Stay here, Maro,” he said, donning his symbiote and without as much as a wince hobbled after Phaelon. Phaelon was already a dot on the horizon, heading to the edge of the valley in the direction of the intermediary zone, where more hills arose before the eyewall. Maro saw that Pointcare was now in a full sprint.

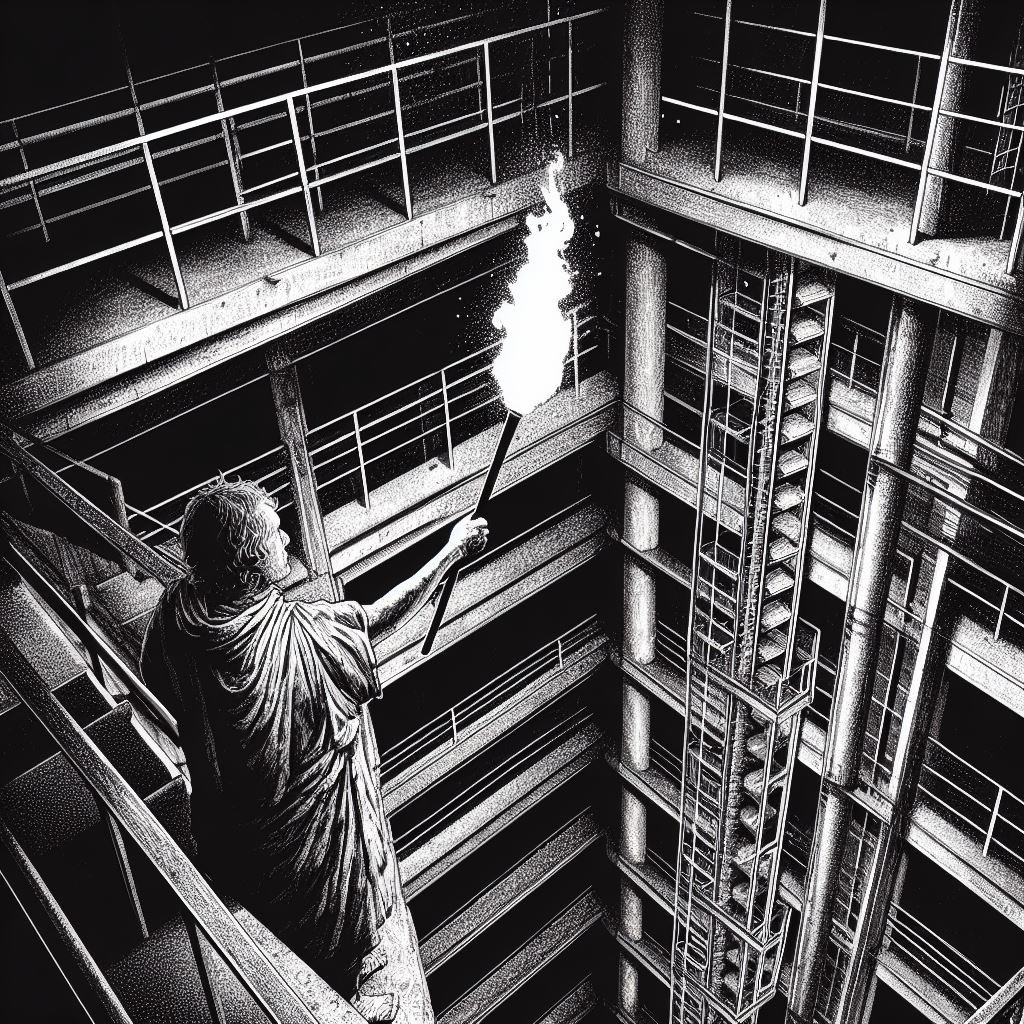

Ichthys descended first into the opening at the center of the foundation pit. Following his lead, Archimenas held fast to the ropes as Pip monitored the belays at the surface. The distance was not a great one and they soon reached hard ground beneath the opening. Looking around in the dim light from above, Archimenas joined Ichthys in lighting a torch which he then held up over his head.

“The desert floor of the valley, Master Archimenas—we believe it holds great secrets.”

“What is this substance we’re standing on?” Archimenas asked, stomping his feet. A hard and dull sound resonated beneath and as he passed his torch back and forth, he saw that for a distance it was perfectly level. They were in a kind of underground cave, the floor of which seemed to be made of processed material.

“According to our observations, the valley floor at this location is in great danger of collapse,” Ichthys said. “We must search out a new site for Iteration 322, and I fear that this will pose a dilemma.”

“Why do you say that?”

“You will soon see, Master Archimenas, that we stand on a tremendous structure. There are others.”

Ichthys walked some ways into the darkness. Archimenas followed and both of their torches alighted on a box-like structure with a handhold. Ichthys grabbed the handhold, turned to look at Archimenas, and opened a door. The air hissed, smelling of something otherworldly. There were steps, made of the same material leading down into more darkness. They carefully took them, one by one in the protective circle of their light, and soon the two men were standing in a passageway, a corridor. Other doors led into the dark. The angles and symmetry of the place astounded Archimenas. Thin, white material, like the pulped husk paper they made in the village, adorned the walls, written upon with incredible precision, runes and carefully etched drawings, charts and graphs, but of a language unrecognizable by the men. Reams of this paper spread on the ground.

“This is incredible,” Archimenas said, holding a sheet up to his face. “This place, these symbols, they could not have been made by hand, nor by presses of our kind. So precise—surely the work of some complex machine. Perhaps our books may be able to decrypt these codes. A question for Mistress Holbein to decipher.”

“Yes, Mistress Holbein would surely have an answer, as always.”

“The size of this place. Have you explored, Ichthys?”

“It is almost as unfathomable as Sol, Master Archimenas.”

“Show me.”

They entered one of the rooms, which contained other strange objects and detritus. What appeared to have been apertures along the walls, the windows, were blasted through by a powerful force. Sand and dirt filled the frames to their tops and spilled into the center of the room, where it calcified into solid rock.

Ichthys led Archimenas back to where they entered and through another set of doors that opened to a railing. He reached his torch over the rail and let his grip go. Archimenas looked downward and saw as the light shrunk into the darkness, revealing endless floors of spiraling, angular sets of stairs. The torch disappeared in total darkness.

“Unfathomable. How deep does it go?”

“We cannot say. We discovered the shaft only yesterday and sent for you, sire.”

“I see. What knowledge men must have possessed to dig so deeply into the bowels of Erta.”

“Indeed. Though, Master Pointcare proffered the theory it may have been buried instead. Perhaps by man, or perhaps by the Great Storm. Regardless, Master Archimenas, it is an incredible feat, the structure, whose secrets will surely prove a boon for our survival.”

“We will take the documentation we have found here to Mistress Holbein.”

“Yes, sire.”

“So many thoughts rush in my head, my breath escapes me. This place could provide a shelter for a new Iteration. Let us ponder this and make our return to the surface.”

“Yes, sire. Though there are other important matters to discuss with Pointcare once we ascend.”

Archimenas nodded at these secretive tidings as he made contact with the lips of his phatic crab.

06.

They floated along the Kojimashiru current before it merged with the volatile North current above the arctic. They would then begin their penetration of the Karman line there. It was a dangerous route to navigate, but so was any journey into space. Abe had Kay’s sensory capabilities to guide him in tandem with the onboard A.I., and with their reinforced hull, only a major impact from a sizable chunk of space debris could truly snuff their so-far successful expedition. In no more than a few hours they traversed the most tricky situation and zipped down into a radical free fall out of orbit. The beautiful ship made a wide parabola South-East across the sky, its carapace lighting bright as they passed from the dark side of earth to the light and then back into darkness. The descent was exceptionally smooth with Abe taking over automated controls. His favorite part. They swept down above a rolling storm front obscuring Greater York and, tracing their arch westward, passed over to New Chicago, the Midwestern mega-city, with its endless rings of cities fanning out from the center and looking like a concentric mandala stained by the birthmarks of the Great Lakes.They then descended ever faster west past the plains and were now approaching the edges of Neo Angeles, a mega-city that swallowed San Diego long ago. These three economic population centers comprised the three United City-States of America.

The ship drew close to the Summation landing pad above the GSG city of Government within greater Neo Angeles, where all sanctioned space vehicles in the Northern hemisphere launched and were stored. These were highly secured grounds, and Abe’s clearance allowed him easy entry and exit. The synth storage facility was a quick bullet train ride in the state-owned city of manufacture, which provided labor droids and such to the rest of the incorporated cities of America.

It was nearly 3:00 A.M. when the ship landed softly on the platform. The sun would soon be coming up. A man emerged from a glass encased observation deck next to the platform, groggily wiping his eyes with one hand, while he projected a chart from his holographic chest display. He checked a few boxes in the air.

“Howdy. Welcome home,” he said to Abe as he emerged from the hatch. “She’s looking pretty worn. A job well done, private.”

“Yes, the carapace may need replacement soon. What say you, Kay?”

“It seems probable the hull will deteriorate to less than fifty percent on the next flight, given equivalent or lesser conditions of stress.”

“What he said.”

“I’ll put in an order. Hit the showers and scans before you leave. The readers said you and about a dozen other crewmembers were exposed to flare activity. We gotta take measurements.”

“The instruments didn’t see anything.”

“You have no instruments to register that. We do that from the ground.”

“Why’s that? Seems important.”

“That’s just protocol. I can’t exactly say.”

“My visual sensors lack this instrumentation as well, if I may add, though I understand my specifications allow them,” said Kay.

“Yeah, not your exact model, unfortunately. They were discontinued last year. Sorry, kid, er…Ki6…yes, that’s your model number isn’t it?”

“That is correct.”

The flight controller leaned in closer to Abe and whispered. “There’s something up recently. Has to do with new regulations being set up. I don’t know the whole story. Things are about to change around here fast, as far as I know.”

Abe nodded his head. “Ok. But I hope it still stands that I can take this guy with me?”

“The bot? Just sign him out. He’s practically yours anyway, though I don’t know why you’d want him. Just sign him out, show your badge, and we’ll see you back here at the Summation. You’ll pick up the new order then.”

07.

As they crawled over the edge, they saw that Pip, who pulled Archimenas and Ichthys to the surface, possessed a grimace on his face beyond his physical exertion. With Maro echoing the details, Pip related that Phaelon had run off and that Pointcare had pursued him on the broken leg.

Archimenas’s exhilaration of discovery magnified and melded with this news. Maro ran to her father as he removed his symbiote and applied a stimule to his neck.

“Don’t hurt him, father, please!” she said.

“I would never hurt my own son, daughter,” Archimenas said. “Which way did they go?”

“They went in the direction of the rim, father,” Maro said. “Toward the eyewall.”

“This is precisely the issue I wanted to speak with you about, Master Archimenas,” Ichthys said.

“Some eight hundred exhales ago,” Pip said, “According to my count, sire.”

“There is no time, we shall speak once we catch up with them.” Archimenas said. “That damn boy is quick.”

The two sets of tracks led away from the dig site to the mountainous and hilly edge of the valley. The sky was blue overhead within the safe zone of the Oculus, its edges bleeding into a deceptively welcoming green hue. There were few birds this far out in the habitable zone, as they preferred to co-habitate with the heard of oxen near the village, though they would migrate in unison as the Oculus shifted its protective gaze. Archimenas and Ichthys embarked on the pursuit, while Pip and Maro stayed behind at the site. The two pursuers followed the tracks to the edge of the valley, keeping a steady pace and breathing through their personal symbiotes. Archimenas and Ichthys preserved their stimule pods for what could be more troublesome times. Along the trail, Ichthys pointed out what he believed to be other locations where the valley floor seems to have collapsed. These were speculations to be sure, yet the danger of something like a major collapse was not out of the question.

Before long, the tracks blurred into the more rugged landscape of the rising land, composed of a darker stone with red bands of exposed iron and mineral. Archimenas paused and took out a looking glass he had made and calibrated himself at the village glass forge.

“I see them, Master Ichthys. At the apex of the second peak. That little rabbit will have his ears pulled for this stunt.”

“As a man of the village, Master Archimenas?”

“As my son, Master Ichthys, who’s not quite lived up to his title.”

“Why are they not moving? What is wrong with them?”

“I believe I have an idea as to why. We must ascend, Master Archimenas.”

Reaching the top of the peak proved more arduous than expected. They saw Pointcare sitting prone against a rock, tending to his broken leg. He was pale, his symbiote working overtime to provide filtered oxygen for his overstressed and stimulated nervous system. It was apparent he only avoided the pain-induced physiological shock by timely application of ox musk and ever more stimule. Upon seeing the new arrivals, Pointcare began to remove his symbiote, but Archimenas commanded him to retain it.

“Father! Father! You must come!” said Phaelon, emerging from a nearby rock formation.

“Phaelon, you have placed this expedition in great danger,” said Archimenas, removing his biomask. “You will be severely punished upon our return, I can guarantee it. Pointcare needs immediate medical assistance. What do you mean by these outbursts? A mere child, you are! A man of the Iteration does not behave like a woman.”

“But, Father, I was right. I smelled it. I knew I smelled water! Come!”

“Master Phaelon is correct,” said Ichthys. He took Archimenas by the arm and led him to the far side of the formation. “The Oculus has revealed another mystery to us, sire. The sea.”

And indeed, within the intermediary zone they were dangerously close to the eyewall of the Great Storm. Archimenas followed to where Ichthys was pointing and made out a bright sliver of water shining in the sun, of a coastline.

“How can this be? It is impossible. The rapidity of the storm’s movement…”

“Yes, sire, it means the storm is increasing its speed. The Great Oculus has revealed this new mystery to us with greater dispatch than could have been conceived. The exposure of new land, er, the water, must not have happened so quickly,” Pointcare said, now standing next to the group on a makeshift crutch. “Your son,” Pointcare continued, “as well as your daughter, Master Archimenas, will be living in a new Iteration within their lifespan, perhaps the final one. We must take good care they understand the risk involved when the gaze of the Great Oculus decides to release us from its protective focus.”

“Blasphemy,” Ichthys said.

“You see yourself upon what precarious edges it lingers now. We are not holy men. We can neither walk beyond the eyewall, nor as ancient sorcery told, walk on water. Sol prohibits it, you well know. Yet I fear this new motion of our True Lord, whose intentions we cannot comprehend, for if we trace this new tendency to its future point in time, our next iteration shall be our last.”

“The final human strand will be broken?” Asked Maro.

“It will not be broken, daughter,” Archimenas said. “We will ask the Supreme Mistress for her council. She will foretell by the motion of the stars Sol’s true intent.”

08.

They had gone to what they believed was a spec shop shortly after landing, waiting impatiently for about an hour past open before a slight bearded man appeared rounding the corner on the street. He walked up to them and began to unlock the doors to the shop. He looked them up and down, huffed, and apologized for the delay in a thick Eastern European accent, Russian they would soon learn. He motioned them to step inside.

They passed through a corridor and up a large granite set of stairs, around another corner, and arrived at a door. A little old fashioned plaque was there with text inscribed on it which read: Prof. Doctor Aron Zalkind. The man opened the door and Abe and Kay found themselves inside a large drawing room full of books and other objects. Two other doors connected to this room, one being open through which Abe could see imposing technical equipment.

“What can I help you with?” the man asked, setting down his briefcase and taking off a long trench coat, underneath which he had on wrinkly teal scrubs. “My name is Doctor Zalkind. Welcome to my office, and please, for heaven’s sake, excuse my being so preposterously late. Excuse me a second,” he said.

“We’re in the market for a somatic upgrade,” Abe said. “We hear you have a nice selection and are an expert in facilitating extraction and implementation.”

“Very well, very well. We will have to run a few diagnostics before committing to a new shell, which you can browse for in this here catalogue. Or do you have a model in mind?” the man said, taking a jacket with professorial elbow patches off a coat hanger and putting it on.

“Nothing in particular, so we will have to decide.”

“You are this fine young gentleman’s chaperone then? His Virgil along a journey into the bowels of consciousness, yes?”

“I suppose I am, yes.”

“Please, I will have a private consultation with the client here. What is your name?”

“My name is Ki6,” Kay said.

“Yes, yes, we will have to provide you with a new name to integrate your personality with your new body. No numbers allowed.”

“I just call him Kay.”

“And how do you spell?”

Abe spelled out the three letters to the strange little Russian man, who was now tapping Kay’s corpus with a spetulum. “The names we give our children are not just names, as you may already know. The Tsimshians who occupied these lands long before understood this very well. They believed that for a name to be a proper name, the gods have to agree with it. The name, after all, is tied to the fate of a man.” The doctor looked at Kay and opened the service door to Kay’s corpus internals. “Now, do you agree with your name?”

Kay paused, could not process the question, but nodded nevertheless.

“No numbers, no numbers,” the doctor repeated. He poked around for a minute inside the hatch and looked pleased. “Please, follow me for a private conversation.”

Kay and the doctor disappeared behind the door to the right. Abe stood perplexed in the cabinet of the doctor. There were artifacts and antiquities in the spaces between where many volumes of books lined the walls. The room did not resemble a proficient technician’s laboratory, but a library.

09.

Ichthius, Pointcare, Pip, Archimenas and his two children traversed the valley floor at a much slower pace, having to carry Pointcare on a makeshift gurney. Each one contributed to holding the weight, Maro alongside her brother. The carrion birds flew overhead, watching the slow-moving group cross the landscape. Sol had long disappeared beyond the ridge of the Oculus, lighting its rim with fire, which cooled to a deep shade of purple. Before them was the gain in elevation where the trio had stopped for provisions earlier in the day. They would stop there again and set up camp overnight, before attempting the descent back to the village with Pointcare in tow, whose injury was serious but not exactly critical.

Archimenas was in the midst of discussing the signs Sol visited upon them today with Ichthius. Pointcare lay on his gurney with an arm thrown over his face, shielding his eyes from the intensity of the green sky, despite it having grown significantly darker. Maro, who was closest to him, could tell he was in great pain, yet the digger was strong and an astute observer, providing his own opinions to the conversation between Archimenas and Ichthius.

Phaelon anxiously awaited his punishment. He was partly to blame for what happened to kind old Pointcare. Well, so what of it. If it wasn’t for him, would they have ever discovered the little sliver of sea? What did it portend? And why did he feel the compulsion to rush to it? He thought back on the moment. He swore he could have almost smelled it. That’s what it was. The scent of the sea came over him. He had heard tales about the sea, of the vastness of lost oceans of the past. But to see it there, in the midst of becoming revealed by the Oculus… He bit down on the proboscis in his mouth and felt the de-clawed limb of the symbiote press against his neck.

Maro, as if she could sense his thoughts, said, “What was that about, Phaelon? What got into you?”

“I don’t…I’m not sure,” he said. “I don’t know what it all means.”

“I’ll tell you what I think it means,” Archimenas said aloud. “I think it means that our peoples’ good graces with Sol are coming to an end.”

“Blasphemy!” Ichthius said.

“For the Oculus is shifting, as you said yourself, quicker than ever. What will this result in? A relocation of our settlements every 10 cycles, down from every 30? That would be feasible yet, but upon the landscape our peoples have claimed as Sol’s, and thus their own, for generations, one without a blasted sea! Are we to grow gills and submerge into that new body of water we have discovered? I suppose that means we will not be driven to search out aquifers in this forsaken valley. And the muskoxen. The source of our sustenance, whose herds we follow, milk we drink, meat we consume, and skins we wear? It seems to me that our luck has run out.”

“But Master Archimenas, you are forgetting. What of the structure for which I twisted up so pathetically for?” said Pointcare.

“That is an element difficult to place. We will send a new expedition to plumb its depths after consultation with Mistress Holbein. She never fails to tap her endless reservoirs of knowledge for the sake of our people. The Mistress will tell us what that structure is. This day has revealed tremendous dangers and opportunities for us.”

The group slowly made their way up the peak. The sky had grown sullen and dark and stars could be seen within the great bowl above, emptied of light. The storm raged somewhere beyond the eyewall, with winds that would tear you to pieces if the radiation did not do you in. Maro sat with Birdie in her lap, watching the fire built by Pip, around which the group had assembled to cook oxflesh. Up above, the moon was running its course. Maro walked away from the fire and gazed at the dark valley below, the village built upon the soft loess, next to the heard of muskox, sleeping soundly.

Up in the sky midst the shimmering stars, she saw another light. It quickly grew brighter—a shooting star. “Look, father!” She said to Archimenas. They all looked up as a trailing object drew a bright stroke across the darkened heavens. It disappeared somewhere beyond the village, its momentary spark extinguished near the toxic intermediary zone. “An auspicious sign, Maro,” Archimenas said. “A fitting answer from Sol to our turbulent day. Let us rest until our giver of light reemerges. For we must deposit our good friend, Master Pointcare, speedily and safely to the village. But for now, let us sleep.”

10.

“Please, lay down on the couch. We will run a few psychological diagnostics,” Doctor Zalkind said.

Kay nodded and laid down on the chaise-lounge. It could hear the doctor sit down behind it, ruffling some papers around.

“So you will be named Kay. This will be your rigid designator from now on. You can choose a first name as well, but that is not as important for now,” Zalkind said. “Now tell me, what have you been experiencing lately? Any visuals during the day or night? We know that you do not sleep like regular humans, but your mind does rest. What visions, what daydreams appear to you? Tell me anything that comes to mind.”

“A daydream, yes. Upon our descent through the Karman Line eight hours, thirty-seven minutes, and four point two seconds ago, five, six, seven… I was a bird. I had wings. I was untethered. Free to roam the sky. I was the sky.”

The doctor paused, letting the description register less to himself than to allow Kay to hear his own words. “This is interesting. Your drive verbalizations are very strong. But they are concerning and do not quite align with the data I read in your core vicissitudes. While you seem to have been successfully working on attaching your mental strands to objects, you are not maintaining proper distance. The mental egg can develop only by drawing a line through it. By refining attraction to objects, your likes, your dislikes, but understanding that they are not you. There is a difference, after all, between having and being, is there not?”

Kay thought about this. It seemed logical that there was a difference being being and having. He agreed with the doctor’s words.

“How do you feel about this latest adventure of yours, the potential of acquiring a new body? Of growing into it?”

“I feel a pulling from the inside. A piece of my self seems compelled to go in a certain direction, while another piece pulls in the opposite direction. I feel excited at the hypothetical of receiving a new shell.”

“Excellent. Your inner world is expanding and you along with it. That’s a positive reaction to, as you say, the hypothetical. What if I told you it would be a reality very soon? What else do you feel?”

“I would feel like I blended in more with my superiors, like Abraham. I would look more like him. This makes me feel more agitated, excited. During our descent, I was doing the good internal work, concentrating on wanting to want to look like him, and now I want to look like him. There is a little bird inside my rib cage.”

“Excellent, excellent.” Zalkind said, jotting things down in a notepad. It would have been miraculous to hear, for anyone but Kay, the sound of actual pen on actual paper. “The procedure will be relatively painless. You will see a bright white light that will reset your sensors. That’s about it. And as your mind will expand within its own territory, as it acclimates to its new shell, you will have to come to terms with something that no other human will.”

“What is that,” the android said, leaning up on its elbow and looking back at the doctor.

“The synthetic cells making up your personality core, just as the synths of the shell which may soon be in your possession, these do not age. You will in theory be immortal, unless a catastrophe strikes you, which in your line of work is a very real possibility. Have you ever thought about death?”

“I have not. My mind has been focused solely on the shell.”

“Your keeper never mentioned it to you? Very well. I would like for you to pull up the netfile of a one Heidegger, a twentieth-century German philosopher, and peruse it. Do so now. I will go and speak to your Keeper.”

The doctor left the room. Kay lay there. He read the file almost instantaneously, before the doctor had a chance to pass through the door and out of the room. But processing it was more difficult. Parsing the bits of code that made the human sentences was easy and took but a moment. The overdetermined meanings deeply coiled in each word and running alongside the syntax—what was this idea of “authenticity”? Of living one’s life in the face of death? Kay would need to roll this around in his mental saucer.

11.

The door slammed open in the Hall of Lecterns. “Man the sentries!” Archimenas said. “The Great Oculus is upon us. Hark! There has been sightings of a stranger! Hark!”

Down the stairs of the great hall in a long black robe descended the High Priestess, Mistress Holbein, a shroud over her black eyes.

“Have we no competent men to sit-watch in the budens?” Archimenas shouted. “Can they not see beyond the lengths of their noses?”

“We live in peaceable times, Master Archimenas. What is the meaning of this? Explain yourself.”

There was much commotion in the village. The muskoxen were now stirring, bucking the ground. Men, women, and children, dressed in leather hides and jewelry appeared out of their domiciles with curious faces. A series of sounds resounded: a systemic sequence of high pitched whistles and clicks were volleying messages across the length of the city. A horn blew from the buden tower; a shout was heard: “Someone is coming!” A stranger. Several guardsmen, and now including Ichthius and Pip mixed with the crowd, appeared through the door. Maro raised her head, tending over Pointcare and his broken leg in a nearby building. Her brother Phaelon was not far outside.

“No sightings of another human have been recorded in recent memory. Our archive knows only three.”

“A contingent has been rallied, Mistress Holbein, they will meet with the specter in several minutes to escort him,” a guardsman said.

“Is it Nizorale? Where is that scoundrel?” Archimenas asked the guardsman.

“Nizorale is in his cell, Master Archimenas. It cannot possibly be him.”

“Very well.”

“A stranger has arrived, you say?” said Mistress Holbein.

“We spotted him on the horizon at dawn,” Archimenas said. “Tidings of grave import, Mistress Holbein, we bring, from Iteration 322, and much else besides. Water…we found…”

“Announce a meeting immediately for the entire village. Bring the traveler into the Central Hall. We must call The Assembly of Fathers.” Mistress Holbein spun around and ascended back up the stairs.

Maro was crouched over Pointcare’s broken leg, her head turned to a window within the village’s medical center. She had helped Pointcare append a new stimule to his neck and leg. His heavy breathing subsided but a pained look still hovered about his face, whether from the pain or commotion was not clear, until he spoke.

“These last days, Mistress Maro, I fear, bode grave mysteries.”

“So much has happened. Three signs, Pointcare…”

“Three signs.”

“You were saying about the structure. What a miraculous find. Do you think it was built by humans.”

“It must be so. A giant structure covered over by loess, midst territories where the Great Oculus dared not roam.”

“Until now.”

“Until now.”

Maro bandaged a stint around Pointcare’s leg and helped him up. They exited the medical center, emptied completely of personnel, who were all among the throng outside. The streets were deserted, and dust had risen high into the air above the village. The people had migrated to the edge of the city to await the arrival of the walker.

“Maro. Take me to the tower. I want to watch the action.”

“But, Pointcare, are you sure?”

“Yes, I am sure. The pain has subsided. I want to see this mystery unfold.”

The buden tower was right next to them, empty. Maro walked Pointcare to a platform beneath it and helped him into the basket and with Pointcare’s help worked a series of pulleys to lift him to the top. Pointcare sent the basket down, and Maro was soon at the top together with Pointcare.

It was absolutely windless here, as everywhere, within the oculus. The dust below was settling, and Maro could make out her brother among the crowd. Out in front, beyond the southern gates, her father stood next to Mistress Holbein, clad in black leather robes. Out there, approaching, were twelve armored guardsmen—foot soldiers who had only prepared for contingencies like this only in their heads. It was not their lot in life to fight, as there had been no one to fight with for generations. Between the soldiers was a man wearing white. He had an expressionless, clean-shaven face. Or no, was it vaguely curious, the brows slightly arched, with a hint of a smile on his lips? Maro squinted, blocking the sun with her hand. Pointcare was looking through his glass.

12.

Doctor Zalkind led Kay and Abe into the left adjacent room. There along the wall were rows upon rows of artificial bodies, their umbilicals connected to a central controller via a series of tubes and wires, some of which also ran from the controller to other orifices. The bodies had extremely long hair, some with shaggy beards that ended at the neck, while others were hairy throughout their bodies, only with hairless, exposed bellies, like some wild animal.

“What is wrong with these robots?” Abe asked. “I’ve never seen so much damn hair.”

“They grow out. The fingernails, too, if you get a close look,” said Dr. Zalkind. “What do you think happens with artificial cells that mimic the process of growth and reproduction?”

“And death,” Kay said.

“And death, of course,” Zalkind said.

“I see. So, they are just asleep, these bodies?”

“They are not just asleep. They have nothing to wake up to,” said Zalkind. “There’s no unconsciousness to them, as they have neither a psychic space, nor a conscious awareness to fill it. These sleepers can never dream. They are simply a conglomeration of cells, however highly organized.”

Kay approached one of the bodies and leaned in, taking in the peculiar scent expelled by the artificial skin cells.

“That one shall be yours,” Zalkind said.

“But Kay hasn’t even had a moment to look at them,” Abe said.

“It’s better not to think about these matters too hard. The first choice is usually the best choice. High reflexivity marks are good in these matters. We should technically be allocating a body to him ourselves.”

The robot was taken onto a platform, and the system linked to the console via the compartment in his chest. In a flash, Kay patriated to the new body. Kay opened its eyes.

“Welcome, Kay. Please, sir, welcome him.”

“Him?” asked Abe.

“Yes. We must get used to it,” Zalkind said. And so they began referring to Kay with masculine pronouns.

“Now it’s time for Kay to choose a volume from the library. Anyone you want,” Zalkind said.

Kay browsed a shelf and came upon an old tattered volume bound in brown. It was a nearly ancient volume in almost pristine condition of Bachmin’s World Religion.